To be honest ladies and gentlemen, this post might turn ugly. Why? Because English Ivy is one of my absolute most-despised plants. EVER. It is horribly invasive, overplanted, and eye-sore, and not to be dramatic, but it’s kind of useless (at least for pollinators and wildlife).

Today, we’re going to talk about how this terrorizer got here, and what we can do about it. Hopefully we’ll spread a little inspiration to get you out in the margins of your gardens, and go yoink those suckers up once and for all.

What’s the Issue with Invasive Plants?

English Ivy thrives in North America’s climate. In fact, the plant is so happy here that it outcompetes the native species who enjoy similar niches. This poses serious problems, not only for the biodiversity of our plants, but also for the insects and animals that rely on native plants for food and habitat.

When plants and animals coexist in an ecosystem for thousands of years, they can develop some pretty specialized relationships. As new, invasive plants come in and take over, those special relationships– and the survival of the plants and animals in them, becomes threatened.

Another, surprising victim of English Ivy’s ravenous wanderings are trees. In abandoned lots, or invaded forests, english ivy can climb up trees and take over their canopies. During the ivy’s climb up the tree’s trunk, tiny roots penetrate the tree bark, dramatically increasing the tree’s susceptibility to disease.

Once their invasion spreads to the treetops, the ivy competes for sunlight. If it gets out of hand, the ivy can eventually topple some pretty sizable trees (think 100-year-old oaks). Unfortunately, this happens all over Atlanta, breaking tree-lovin’ hearts everywhere.

How did English Ivy get to North America?

English Ivy (Hedera helix) is not a native to North America, it’s native to Western and Central Europe, and North Africa. How did this pesky plant travel so far?

Given the plant’s common name, you may have guessed how it got here. Yep, those globally infamous colonial settlers, the English. In the 1700s, the plant had value as a low-maintenance groundcover. So, it was imported from Europe and planted far and wide along the Atlantic coast. Lucky us.

Perhaps we can appreciate the irony of how many resources are sunk into mitigating the damages of this “low-maintenance” landscape plant.

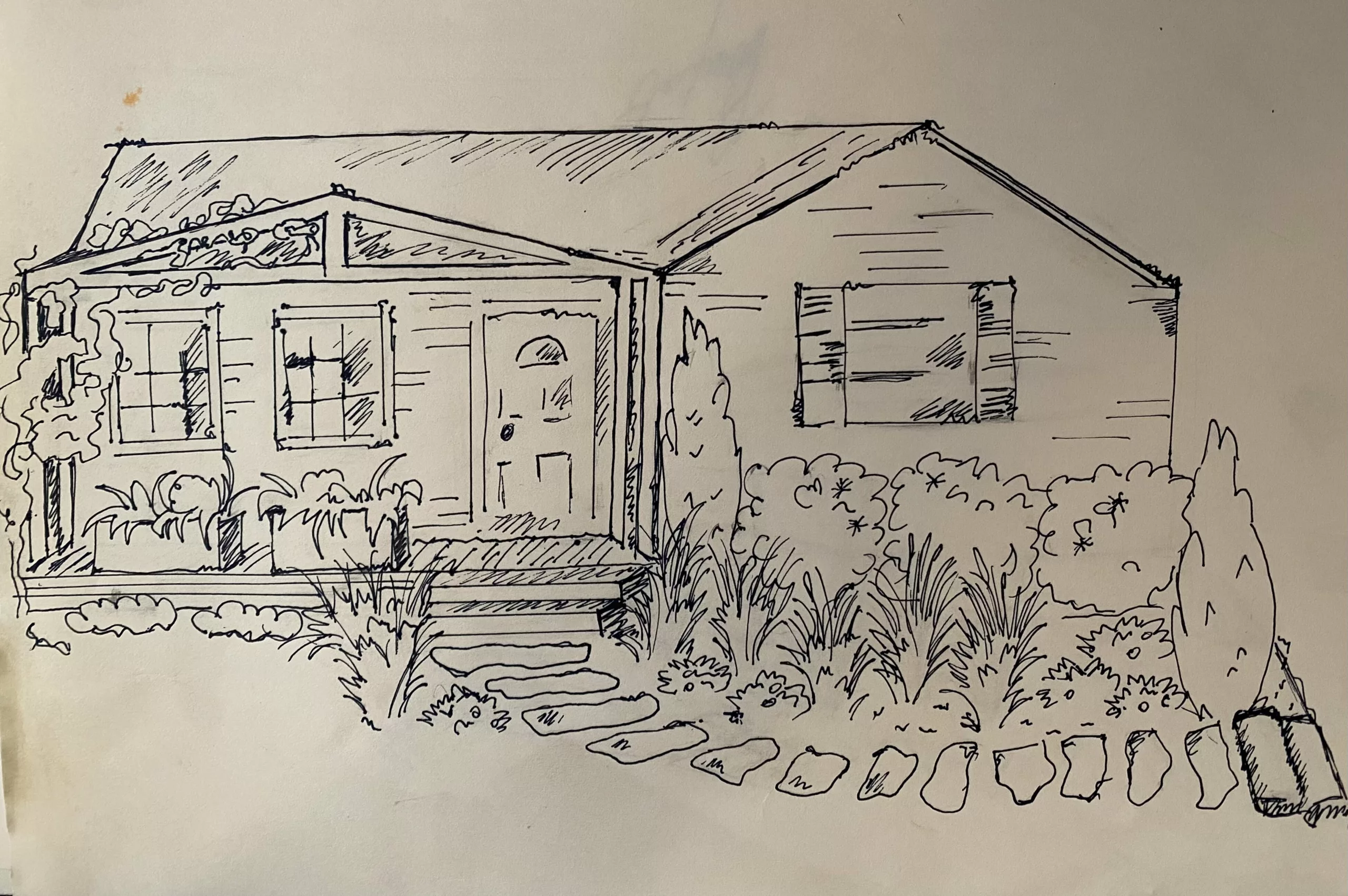

English Ivy Description

If you think you’ve never seen English Ivy before, you just may not have known what you were looking at. I promise you’ve seen it.

The pernicious invasive plant grows everywhere. Open fields, forests, roadways, the side of buildings, fences, and disturbed areas. Throughout the East, West, and Midwest of the United States, English Ivy is ubiquitous.

Its glossy green leaves are tri-lobed and deeply veined. Their roots tend to remain shallow, and they can propagate asexually from pieces of these roots, or sexaully from seed.

English Ivy removal

Removing invasive plants is time consuming– due to their reproductive methods, removing every piece of root is critical– however, it’s incredibly important to protect other plants and wildlife.

As the Ivy spreads, it may climb tree trunks, or old buildings.

When it grows on trees, the ivy causes issues by keeping the tree bark moist, and the micro injuries its roots cause only make the tree more susceptible to fungal damage. Compounded with English Ivy’s tendancity to carry a fungus that destroys tree leaves, an ivy infestation can spell a slow and painful death for mature trees.

Buildings can also face thousands of dollars in damage if ivy takes over. Similar to its effect on tree trunks, English Ivy keeps the sides of the building moist, resulting in rot and mold damage.

To remove English Ivy from mature trees or buildings, make sure to pull it down carefully. Anything that seems super tangled, leave up there (for now). Once you’ve pulled down some hefty chunks, you should have a pretty good idea of where the soil-rooted part of the plant is.

Remove as many soil-living roots as possible, and cut the rest of the ivy away from this main root ball. In a few weeks, that tangled up ivy should be dried up and dead. Now it’s safe to pull those suckers down and say “adios!” for good!