There are several new buzzwords in gardening that I think do a disservice to gardeners. These hard-to-define, emotionally charged terms such as “native” “invasive” and “non-native” have made gardening a politically correct nightmare. Many home gardeners have asked, “Is it ever OK to plant non-native plants?”.

While promoting biodiversity is always a benefit to Planet Earth, these antagonistic words can detract from our gardens. Are all non-native plants “invasive” and “bad”?

There are non-native plants which do a better job satiating hungry pollinators than some of our native plants. There are native plants that become invasive, and there are native plants that can no longer thrive because their environments have been too disturbed by human activities.

These issues make us ponder what is “safe” and “good” to plant, versus what is “bad” and “unsustainable”. Our solutions deserve as much nuance and consideration as we find in the garden of Mother Nature.

Defining Terms

Native Plants

This first term is perhaps the easiest to define. According to Webster, Native means “inborn, or innate”. So, a “native plant” is simply any plant whose origins are from the area in question.

This gets tricky when we expect plants to behave according to map lines. Trying to decode “native plants in Georgia,” “native plants in the Midwest,” or even “native plants in North America,” can get pretty hairy.

Realistically, we will never know exactly where a plant originated from. Mostly because human activities were disrupting plant communities long before we thought to label what is native or not.

(Though, there is a lot of great research currently being done to investigate what plants lived across North America before Europeans arrived. )

Non-Native Plants

You may have guessed this next definition– Non-native plants do not have origins in the geographic area in question. However, this does not mean they are invasive or damaging to their new ecosystems.

Some non-native plants become naturalized. Meaning that they integrate into the ecosystem without a gardener’s interference. The key distinction between a naturalized non-native plant and an invasive one, is that naturalized plants do not cause major harm or disruption to the biodiversity of the place.

For example, near my home in the Central region of North Carolina, there were often Spring daffodils blooming in the forest. No one planted those flowers there, and they only ever occurred in small patches. The Daffodils had been adopted by the forest, and didn’t actively compete with other wildflowers.

The lovely yellow Daffodils contrast greatly with this next cohort of plants…

Invasive Plants

Invasive plants are introduced to an environment, naturalize rapidly, and then begin to wreak havoc on other plants.

A prime example of an invasive plant is the notorious English Ivy. (Check out this post for a hilarious and informative read about my “favorite” invasive plant.) Not only does it reproduce in an environment, it does it so quickly that it outcompetes and kills off the local plants.

That’s not to say invasive plants are all bad. Some of North America’s invasive plants, such as Plantain (originally from Europe) and Mimosa trees (originally from Asia) are edible and medicinal. In fact, these two examples even made their way into the pharmacopeia of several Native American Nations.

The real tragedy of invasive plants is their detriment to global biodiversity. Biodiversity helps keep our ecosystems balanced and resilient. When a species of plant, insect, or animal goes extinct, it is a total loss that is completely irreversible.

Is It OK to Plant Non-Native Plants?

First and foremost, the answer to this question can only be answered by the gardener for his or herself. I’m here to simply offer my opinion and hopefully get your gears turning.

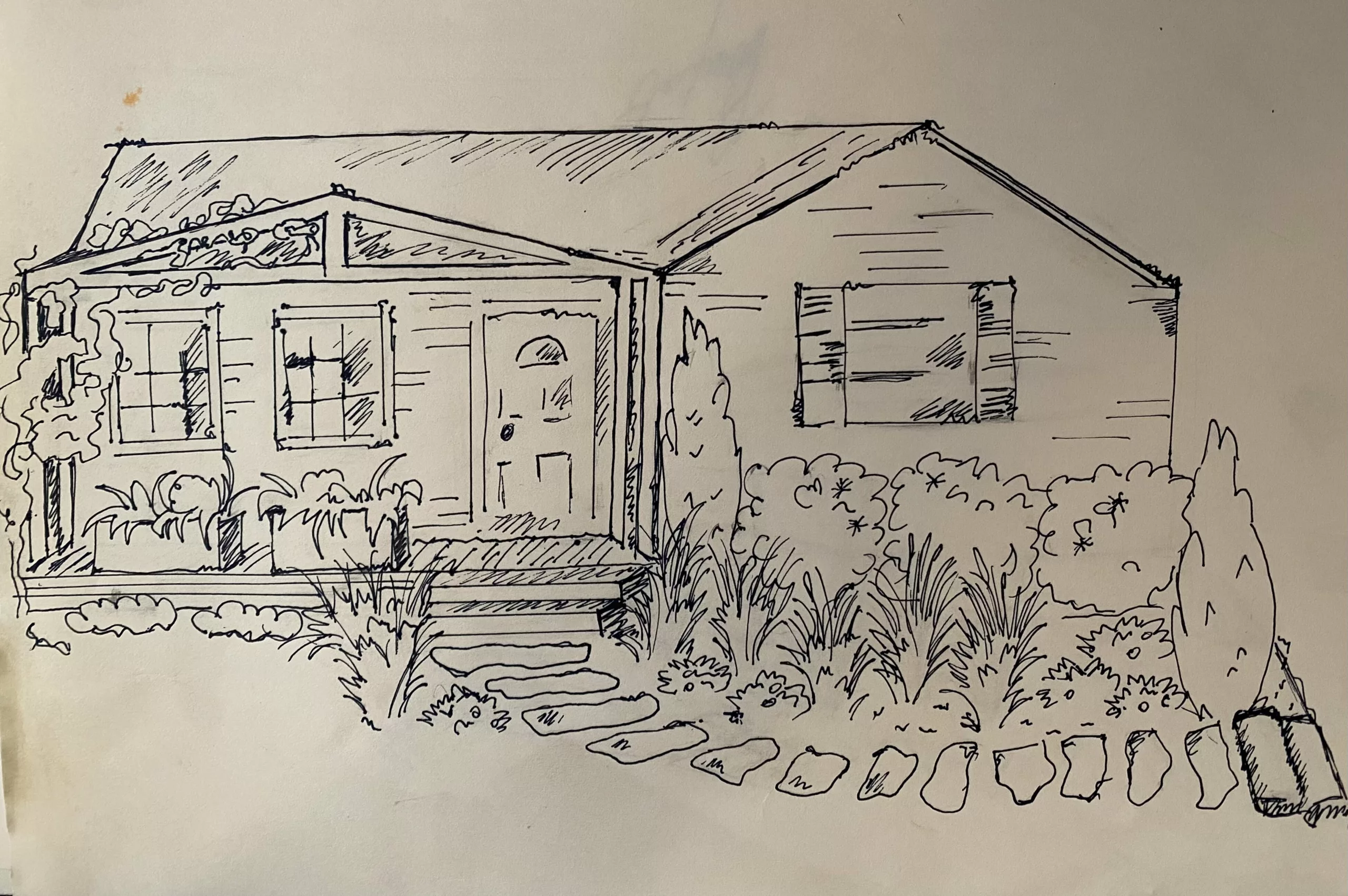

Whenever considering planting non-natives, I would urge any gardener to ask if they could substitute a native plant in their place. A great example of where these substitutions are useful is in cut flower gardens, rain gardens, and foundation plantings.

Vegetable Gardens

Yet substituting native plants can be a much trickier task when planting fruit trees, or annual gardens meant for food or herb production. Who wants to sacrifice their peach trees or apple trees, their carrots or lettuces?

Luckily, many popular food annuals are actually native to the Americas. This includes corn, pumpkins, several squash and green bean varieties, potatoes, sunflowers, and tomatoes. If you haven’t tried planting these, put them on your agenda for the next spring garden!

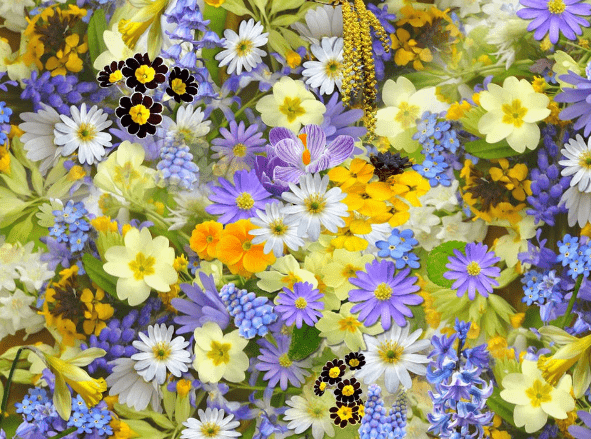

Pollinator Gardens

Planting an all-native pollinator garden can get tricky as well. Sadly, there are many native pollinator plants that just won’t grow as well as they used to. Why? Some plants can’t cope with the environmental pollutants in the air, water, and excess light from cities and suburbs.

In addition, there are some non-native plants which provide better nourishment for some pollinators than their native counterparts. It’s important to do your research. Some of these nectar laden plants may be a great food resource, but not habitat. Finding balance between the two is crucial for any good pollinator garden.

Now, this is not condoning the planting of a myriad of non-native plants in your pollinator garden. I’m simply saying that a little research can help us find the best in all plants– as long as we plant responsibly.

Conclusion

All plants, and all people, are native to the one-and-only Planet Earth. But it is true that not all plants (or people) work together and play nice when introduced to a new environment.

As eco-conscious gardeners, we have a responsibility to educate ourselves about plants– not just put them into boxes of “good” or “bad”. It’s up to us to understand how and where each one can fit into our environments.

Be sure to continue learning and do your own research, make your own decisions, and plant the garden that makes you, and the planet, the happiest and healthiest it can be.